Georges Seurat 19th century anarchist pointillism; Damien Hirst's 21st century nihilist Spots

(Return to Part IV)

"Bourgeoisie" and "proletariat" are terms that may still have a certain amount of currency among a set of cultural theorist and political activists, but for most of us they are badly dated terms, especially in the case of proletariat, which few people use except in boldly debarked air-quotes. "Bourgeoisie" has a little more currency left because it still gets thrown around as an insult. The Parisians call hipsters BoBos (Bohemian Bourgeoisie). We all can picture someone, some place, or some event as being "bourgie" - even if we don't know exactly what it means, we know contempt is being expressed and that it has something to do with material wealth and comfort. But even if most of us no longer think of ourselves primarily in terms of class, these remain powerful frames, that shape the ways we think. At exactly the same time as workers and capitalist differentiated themselves from peasants below an aristocrats, artists came into their own as a highly regarded group outside of class, producing objects that were understood to be separate from the market forces that defined the classes art was understood to be outside of.

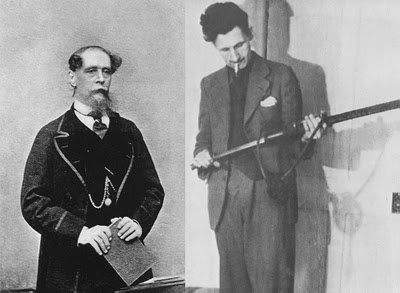

Both bourgeoisie and proletariat are antebellum terms, but they may as well be antediluvian; describing things that existed before the Bolshevik revolution threw everything into doubt, WWI cut what was left to pieces, and the Great Depression burned reduced the remainder to rags and ash. Consider George Orwell considering Charles Dickens; two artists separated by the flood of those upheavals; already the flora and fauna of Dickens' thinking were as strange as Australia to Orwell.

Dickens holding a book; Orwell holding a gun

In 1940 George Orwell began

an essay on the subject of Dickens by observing, "It is not merely a coincidence that Dickens never writes about agriculture and writes endlessly about food. He was a Cockney, and London is the centre of the earth in rather the same sense that the belly is the centre of the body. It is a city of consumers, of people who are deeply civilized but not primarily useful." Here we have the beginnings of the confusion between the bourgeoisie and the consumer. But Dicken's world is not our own. Consider Orwell's main complaint against Dickens: "In Dickens's novels anything in the nature of work happens off-stage." Orwell had a relatively clear view on the immediate bourgeoisie past of Dicken's 19th Century:

The vivid pictures that he succeeds in leaving in one's memory are nearly always the pictures of things seen in leisure moments, in the coffee-rooms of country inns or through the windows of a stage-coach; the kind of things he notices are inn-signs, brass door-knockers, painted jugs, the interiors of shops and private houses, clothes, faces and, above all, food. Everything is seen from the consumer-angle.

And while Orwell name-checks "the consumer" and seems to feel he has a view on this emerging economy as well, it was not just a foreign country for him, in 1940 consumerism was an unexplored frontier - only truly flowering in the postwar years after his death. Aesthetically, Orwell clearly admires Dickens, but ideologically, finds his limits contemptible. "No modern man could combine such purposelessness with so much vitality" Orwell writes. Pointing out that while Dickens lived through the Industrial Revolution, and resided within its epicenter, "Dickens nowhere describes a railway journey with anything like the enthusiasm he shows in describing journeys by stage-coach. In nearly all of his books one has a curious feeling that one is living in the first quarter of the nineteenth century, and in fact, he does tend to return to this period."

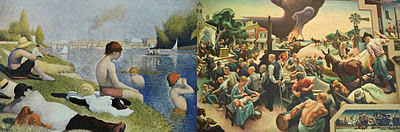

The Public Sphere as leisure and as work: The Anarchist George Seurat, Bathers at Asnieres (1884); The Socialist Thomas Hart Benton, A Social History of the State of Missouri (1936)

For better or worse Dickens' imagination had fastened on to the waning years of the Enlightenment, before any kind of deal had been struck between a growing bourgeoisie elite and an even faster growing proletariat work force. These were wildcat years for capitalism; an era of child labor, debtor's prison, and work houses. Orwell faults Dickens for being a progressive without any sort of program for reform: "he attacks the current educational system with perfect justice, and yet, after all, he has no remedy to offer except kindlier schoolmasters." By the end of WWII, just 5 years after Orwell was writing, the worst of the conditions Dickens wrote about, the near slavery, murderously unsafe factories, endless workdays, and septic urban slums - had, by and large, been successfully reformed in the industrialized world.

By 1945 most industrialized nations had some form of socialized healthcare for workers and other forms of welfare that (even the US) protected failures from a drop into abjection. Until the end of the 19th century, capitalist economies had attempted to do without these sorts of "safety nets"; demands that were repeatedly made by workers and had repeatedly (and violently) been refused by Industrialists; but even before the Bolshevik Revolution, important concessions had been made in every aspect of the industrial economies of Europe and the US.

Edgar Degas, Absinthe Drinker (1876); Norman Rockwell, Rosie The Riveter (1943)

The course correction by Modern states threatened by the danger of a workers revolt were not made by soft hearted altruists - men like Bismarck and his royal creature Wilhelm II, were hard fought, but they were profound. Gains continued to be made during the Great Depression, but as

Richard Wilkinson documents, it was the years of WWI and WWI when workers made the greatest strides and income inequality shrank the most in Industrialized countries.

What is most remarkable about Orwell's essay is not how alien Dickens is, it is how alien Orwell is. He belittles James Joyce for spending a decade on a novel about the "common man" that ends up being about a highbrow "Jew." And as familiar as his contempt for Dickens' foodie preoccupations may seem, he complaint wasn't that Dickens is a pretentious aesthete, or that he out of touch with the realities of what most people can afford, or even that Dickens is oblivious of the production system his dining requires. Orwell was complaining that Dickens is out of touch with manual labor. "He has an infallible moral sense" writes Orwell, "but very little intellectual curiosity. And here one comes upon something which really is an enormous deficiency in Dickens, something, that really does make the nineteenth century seem remote from us — that he has no idea of work."

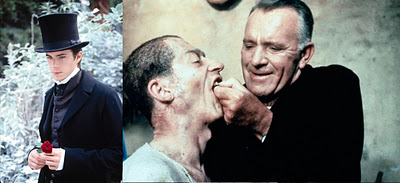

Men without chests vs men without Teeth: Dickens' Nicholas Nickleby and Orwell's Winston Smith

Orwell is aslo critical of Dickens for lacking interest in violence: "Considering the age in which he was writing, it is astonishing how little physical brutality there is in Dickens's novels... he sees the stupidity of violence, and he also belongs to a cautious urban class which does not deal in socks on the jaw, even in theory." This isn't simply an indictment of Dickens for some brand of intellectual dishonesty (refusing to show some harsh reality), Orwell finds Dickens soft; domestic; effeminate:

This is the type of the Victorian happy ending — a vision of a huge, loving family of three or four generations, all crammed together in the same house and constantly multiplying, like a bed of oysters. What is striking about it is the utterly soft, sheltered, effortless life that it implies. It is not even a violent idleness, like Squire Western's. That is the significance of Dickens's urban background and his noninterest in the blackguardly-sporting military side of life. His heroes, once they had come into money and "settled down", would not only do no work; they would not even ride, hunt, shoot, fight duels, elope with actresses or lose money at the races. They would simply live at home in feather-bed respectability, and preferably next door to a blood-relation living exactly the same life.

Ends of History: Orwellian vs Neocon

I share Orwell's confusion at the idleness of the bourgeois ideal. But bridle at his contempt for consumers, "of people who are deeply civilized but not primarily useful." Orwell died in 1955, he didn't live long enough to see consumer culture, to witness the sort of work men, at once vulgar, and yet with no interest in "blackguardly", would do. To see how different they would be from a Snodgrass, Chuzzlewit, Pickwick, or a Nickleby. The end of history isn't peopled with virtuous hard fisted men with eyes to real work, it is overstuffed with the "deeply civilized but not primarily useful"; consumers are as different from the bourgeois as anyone had hoped, or feared, the communards would be. The big difference is consumers aren't capitalists, they work for a living.

According to Orwell, "in the typical Dickens novel, the deus ex machina enters with a bag of gold in the last chapter and the hero is absolved from further struggle... The ideal to be striven after, then, appears to be something like this: a hundred thousand pounds, a quaint old house with plenty of ivy on it, a sweetly womanly wife, a horde of children, and no work." This is the ideal, at the end of the 19th century, of a class that emerged at the end of the 18th - a class that depended entirely on capital gains for their comforts. At the end of the 20th century this class began reconstituting itself. Mitt Romney and his Wall Street peers lobbied to be

taxed at rates fare lower than Americans whose income comes from labor. The high prices commanded by art stars like Damien Hirst are often pointed to as an indication of artworld dysfunction. However, Hirst, who's rise accompanied Romney's, is in perfect step with his neo-liberal counterparts. While the bourgeois ideal may sound like the life most consumers hope for, and Hirst's highly branded art may look like consumer commodities, both are at odds with the economy that took shape in the years after Orwell's death. (To be continued...)

Shit is Fucked Up: Romney joking about being unemployed with a group of unemployed workers; Damien Hirst, The Golden Calf (2008)

No comments:

Post a Comment